Two years after devastating floods submerged a third of the country, killing more than 1,700 and impacting 33 million more through the loss of infrastructure, homes, livelihoods, livestock, and crops, Pakistan stands at a crossroads in disaster response. The CGIAR Initiative on Fragility, Conflict, and Migration (FCM), co-led by IWMI, spearheads innovative research to enhance anticipatory action and address vulnerabilities in host communities.

Climate change compounds the myriad challenges already faced by Pakistan—poverty, population growth, resource scarcity, infrastructure challenges, and political instability. Ranked as the 8th most vulnerable country to climate change globally, Pakistan grapples with the impending impacts on agriculture, food security, and economic development, with the agricultural sector bearing the brunt [1].

In the wake of the devastating floods in 2022, an estimated 8-9 million people slid into poverty [2]. As the country combats the increased frequency of extreme weather events like floods and drought, a growing phenomenon of climate migration has emerged, both because of and as an adaptation strategy to climate change. Events like flooding mean many rural communities face displacement and are forced (or choose) to migrate to cities or other regions in pursuit of alternative livelihoods. The recent disasters have highlighted Pakistan’s desperate need to reinforce climate defenses, especially in adopting systemic approaches to mitigate water risks in the Indus Basin. There is an urgent need for improved risk identification and quantification to highlight the most vulnerable areas and assets across all levels.

Climate-induced displacement and migration is a growing trend which needs attention

In 2021, disasters were the leading trigger for internal displacements in South Asia, with 5.3 million people displaced, and 70,000 internal displacements recorded in Pakistan [3]. Climate modeling estimates that by 2050 Pakistan will have nearly 2 million climate migrants within its borders [4]. While there is growing evidence that climate change contributes to large-scale migration, further research is needed to understand the extent to which climate change drives migration and what the vulnerabilities are of migrant communities and the host communities who receive them.

Trends in Pakistan suggest that displacement is often temporary, and many people do return to their homes. While disaster-induced migration tends to be short-term, slow-onset climate-induced migration may be more permanent and on a larger scale. These are nuances which current data in the country simply do not capture, including how climate change interacts with other factors like social, political, economic, environmental, and demographic influences. For receiving communities, the influx of migrants may place additional strain on local infrastructure, exacerbating pre-existing issues related to water and sanitation. This compounding effect further burdens essential resources and underscores the interconnected challenges faced by both migrating populations and their host communities.

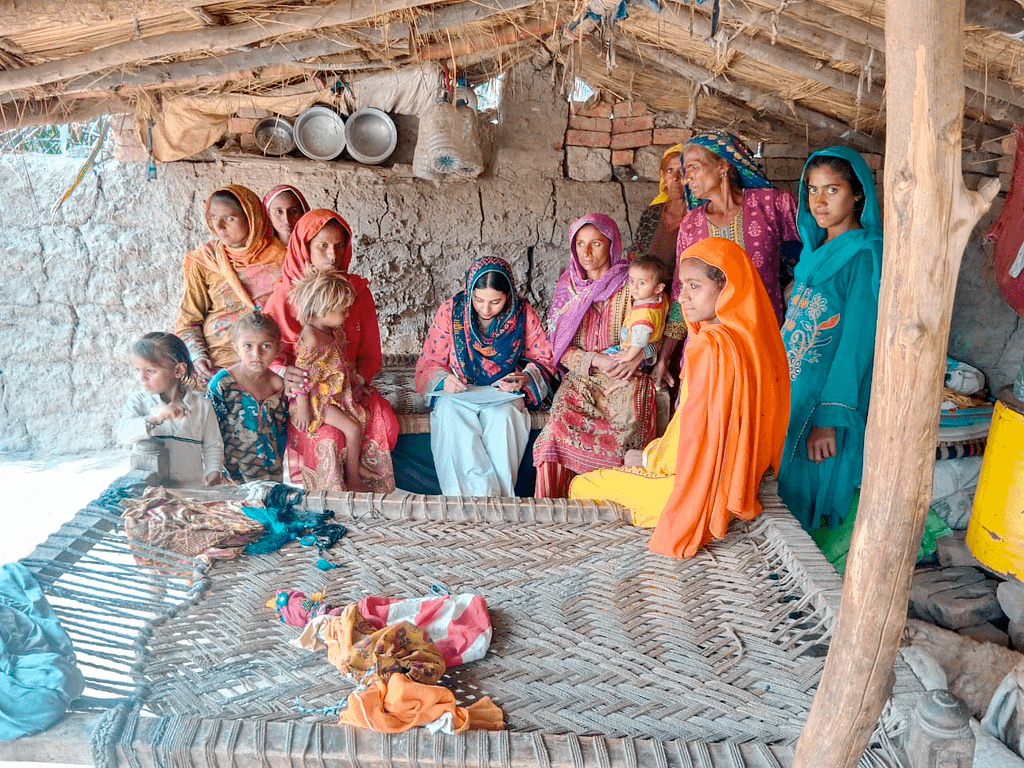

The Fragility, Conflict, and Migration (FCM) Initiative aims to address some of these data gaps and respond to the challenge of disaster response and management. Pakistan serves as one of the case study countries under the Initiative, where the IWMI team is conducting research to unpack the layered challenges faced by climate migrants and the parallel vulnerabilities experienced by host populations. Gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) considerations play a key role in our analysis, as disasters impact men, women, and children differently [5], [6], [7].

The team is examining how sudden and unplanned migration, triggered by climate-related events, places additional stress on already strained resources in host communities. Leveraging IWMI’s technical expertise, we are examining impacts on food, land, and water systems (FLWSs) and resulting economic, social, public health, and environmental tensions. Part of our research also examines the role of digital inequality in disaster response. Despite the potential for technology to be leveraged during disasters, initial findings show a notable gender gap in mobile phone usage and access to internet.

The case study area, Rahim Yar Khan (RYK) district in southern Punjab, presents a microcosm of climate vulnerabilities. As a host community – receiving an influx of climate migrants from neighboring Sindh and Balochistan provinces – and a district at high risk to various natural hazards like drought and flood, RYK offers insights into the multifaceted impact of climate change on FLWSs, economic dynamics, and social and environmental tensions.

Government partnerships are also a key foundation of the FCM Initiative in Pakistan. IWMI team is working with the Federal Flood Commission (FFC) under the Ministry of Water Resources for understanding flood impacts on local communities in Rahim Yar Khan. We are also collaborating with the Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD), Government of Pakistan for a better understanding of drought impacts on local communities. The study findings will be used by these relevant government agencies, including the Planning and Development Commission of Punjab province, the National Disaster Risk Management Fund (NDRMF) and the Provincial Disaster Management Authorities (PDMAs), for preparing evidence-based anticipatory actions for dealing with future disasters, particularly for climate-displaced migrant communities and receiving communities at provincial and local scales.

What do you do when there’s no data on climate migrants to begin with?

Focusing on climate migrants, our initial research step was pinpointing these communities. With limited data available, our team collaborated with a local NGO for a district-wide scoping visit to identify climate migrant “hot spots.” In October 2023, we deployed a rapid migrant identification survey, identifying key migration factors, livelihood impacts, early warning information, origins, and return plans. Around 500 climate migrants were identified, the majority displaced due to flood. From this preliminary scoping visit, we have identified areas across the district where displaced households are currently residing. This is one of the first attempts at systematically collecting disaggregated data specifically on disaster displaced communities in Pakistan at the district level.

What’s next on our research journey?

Moving forward, the team is working on completing and analyzing site surveys, focus group discussions, and key informant interviews to understand disaster responses, early warnings, and preventive measures. This data will be the backbone for identifying vulnerability hotspots, correlating them with climatic changes and evolving patterns in food, land, and water systems. By analyzing diverse data sources, we aim to enhance our understanding of migration dynamics, exploring individual motives and impacts on local water and food ecosystems. The team plans to establish hotspot sites for future vulnerability forecasts, anticipating climate-induced migration across vulnerable areas. The team is proposing an actionable roadmap for the inclusion of women and youth and the provision of knowledge products and advisory services to at-risk communities. The findings contribute to the development of new government policies for risk reduction measures such as strengthened early warning systems and enhanced emergency planning and response capacities. The ultimate goal is to develop a nuanced anticipatory action learning framework, with findings scalable to other districts across Pakistan, tailored to the unique challenges posed by climate change.

Sidra Khalid is a National Researcher – Gender and Social Inclusion, International Water Management Institute (IWMI); Hafsa Aeman is a Senior Research Officer – Geoinformatics, IWMI; Kanwal Waqar is a Researcher – Gender and Youth Specialist, IWMI; and Mohsin Hafeez is Director of Water, Food and Ecosystems, IWMI.

This story originally appeared on the CGIAR website.