An interview with Dr. Karen Villholth – Principal Researcher

By Clara Colton Symmes, Princeton in Asia Fellow, IWMI

The world holds massive underground reservoirs of water – even in some of the most arid regions – that have the power to transform the lives and livelihood of millions of people, especially in times of drought. We must not undermine this resource.

The theme of this year’s World Water Week is “Building Resilience Faster”. Dr. Karen Villholth, Principal Researcher and coordinator of the groundwater program at IWMI and the Groundwater Solutions Initiative for Policy and Practice (GRIPP), collaborates on a number of projects that aim to do exactly that.

In her over ten years with IWMI, Dr. Villholth has dedicated much of her time to promoting the wise use of groundwater, especially in Africa. Beyond her work with GRIPP, her current projects include the Sustainable Groundwater Development and Management for Humans, Wildlife, and Economic Growth in the Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA-GROW), Groundwater for Resilience in Africa (GRAN), and Enhancing Sustainable Groundwater Use in South Africa (ESGUSA).

At World Water Week, she hopes to bring attention to groundwater as a resource to use and protect, particularly through sessions promoting GRIPP, KAZA, and AMCOW, and their Pan-African Groundwater Program (APAGroP).

As the head of the GRIPP partnership, Dr. Villholth focuses on human-groundwater relationships and challenges. She works to build capacity and create policy for groundwater management as a means to effectively, sustainably, and equitably enhance resilience, agricultural livelihoods, and quality of life with the aim of embedding groundwater more fully into the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

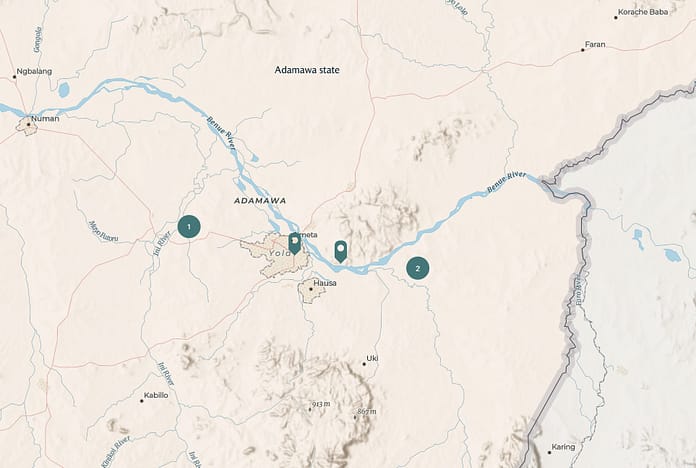

The KAZA is a multi-lateral cooperation on transboundary resource management in the largest transfrontier conservation area in the world. It was formed to improve the management of tourism, livelihoods, and sustainable development in parts of the Kavango and Zambezi river basins, where Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe meet. Through this process, national and international leaders realized that water is becoming an issue requiring specialized attention, and Dr. Villholth and an IWMI team have been supporting the efforts with focus on the transboundary groundwater aspects.

Developing groundwater locally so that it caters to both humans and wildlife, and at the same time avoids conflicts during times of drought is becoming a first-line question for the region. “The issues [surrounding transboundary groundwater] are common and familiar,” she said. “It’s a shared resource, so at the end of the day, different countries will be claiming the water because they need it. So how do you do that in a collaborative, climate-smart, and sustainable way?”

In a recent interview, Dr. Villholth spoke more about IWMI’s groundwater program and how events such as World Water Week are important to protecting and managing the resource. Read more from the interview below.

What is groundwater exactly? And why is it so important?

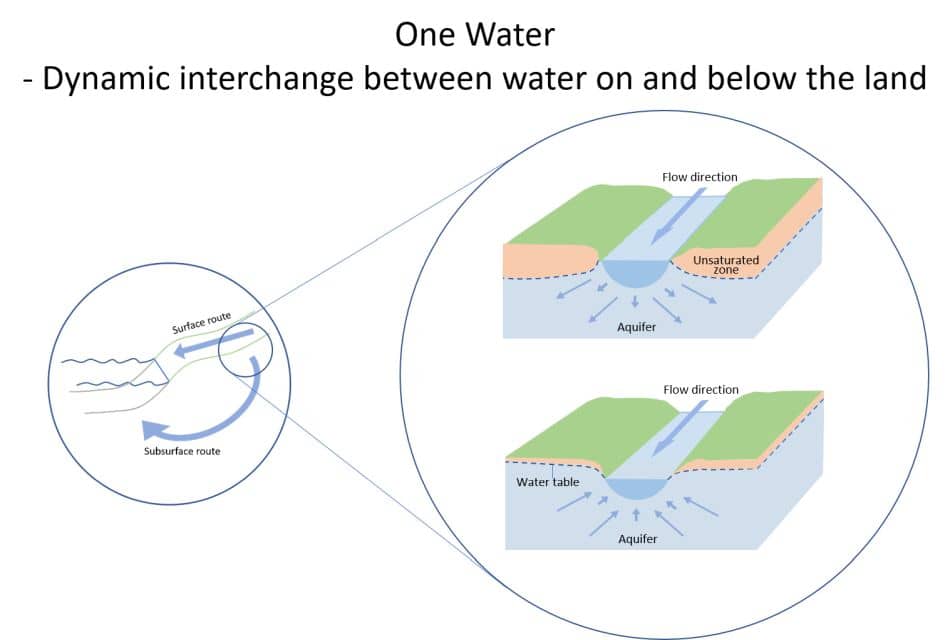

Groundwater is part of the hydrological cycle. In arid landscapes, bodies of water like lakes or rivers provide passive recharge, or if there is rain during part of the year, then some of it will soak into the ground and be stored there. While part of the same “one water,” we give groundwater a special name because it’s accessed differently; it’s available pretty much anywhere at any time and it’s usually good quality. If you have means to drill a well, you will likely find water under your feet. Even during droughts, it takes a long time before groundwater is impacted. It’s like a protected storage of water that won’t evaporate. And that’s what makes it so compelling for climate change adaptation and resilience.

So, there is groundwater even in the most arid parts of the world?

Yes, and the amount of water does not necessarily correspond to the rainfall, because for instance, in the Sahara, you can find a lot of groundwater in deep aquifers. It was laid down in a previous historic time when there were different weather patterns there. Since then, the climate has changed, but the water is still there, and not in small amounts – it’s one of the largest underground reservoirs of water. It’s very important for urban and rural people living there, who are drilling for it now and farming with it, among other uses.

What are the greatest threats or challenges facing groundwater?

Since anybody with the means can access groundwater anywhere, there’s a tendency to develop it quite substantially, so there is a risk of depleting the resource. We are seeing this especially in semi-arid regions where there’s a lot of agriculture that relies on irrigation. If you take too much of it, then it doesn’t have the drought-proofing capacity anymore. If there is a drought, then there is a big problem. This is what is seen around the world today, even in places like California.

Groundwater also faces the threat of contamination from agricultural use of fertilizers and pesticides, dump sites and poor sanitation systems. This issue may become even more critical as we go forward, as groundwater contamination is difficult to remediate, especially for resistant or constant-load contaminants. We need to think about the chemicals in our products and how we can reduce their use for the sake of groundwater, as well as how we can more effectively recycle, protect our waste sites, and plan our land use.

How do programs like GRIPP address these threats and challenges?

GRIPP addresses groundwater issues in a developmental context. In other words, issues that relate to human interactions with the resource. GRIPP aims to identify possible solutions to these challenges that will benefit everybody. For instance, with our partners and collaborators we’ve been looking at managed aquifer recharge and other groundwater-based natural infrastructure solutions, which enhance the natural role and services that groundwater is already providing, but in a way that improves water security, and human and ecosystems resilience.

How can the KAZA project’s successful transboundary water resource management act as a model for other regions?

The KAZA leadership and partners have been very upfront in terms of getting water on the agenda for sustainable conservation and development in the region. They are not shying away from addressing it, seeing that it’s important for humans, ecosystems, and wildlife. I also appreciate that they have taken on groundwater as a very critical issue because they see that it’s value for people and wildlife will increase in the future.

Why are events like World Water Week important in ensuring water security?

These global events bring together stakeholders from around the world to address joint challenges with different perspectives. That’s where you find partnerships and explore solutions as well as engage stakeholders in and outside the water sector. We’ve used it to highlight the importance of groundwater. And I think it’s becoming more mainstream, a result of the growing need to use the resource sustainably during climate change and population growth. And I think, with next year becoming the UN Year of Groundwater, we are setting the stage for that with this year’s World Water Week.

What does the UN Year of Groundwater mean for groundwater research and management?

Every year, UN Water identifies a new focal topic related to water and then it is up to partners to move forward with it as a platform to highlight and address issues. Its success depends on methods of global engagement with scientists, political decision makers, and the public. Success will look like having groundwater use and management becoming common knowledge and part of joint action, e.g., as part of the global agenda on climate and food security.

What are your goals for participating in World Water Week?

With KAZA, I have a very clear goal: to further promote the integration of groundwater into conservation strategies, and to attract more funds for some of the specific work that is critical to better understand the groundwater resources in the KAZA. It’s also about building partnerships where I can be a resource for knowledge and evidence for stakeholders. With GRIPP, I’m aiming to further the understanding of and attention to groundwater at various levels in the scientific community and at the political level. With AMCOW, we are aiming to insert groundwater at the highest political level in Africa, to make it part of continental and national development strategies.

What are your hopes for water system science as IWMI becomes part of the One CGIAR?

One CGIAR gives IWMI the opportunity to put water centerstage on the sustainable food systems agenda. We must see water as a critical component of sustainable food production and consumption patterns. I think we should use the current dialogue around global food systems to enhance our agenda on water, including that of groundwater.

What makes you feel hopeful about the future of water systems and groundwater?

I see some progress, and this gives me hope that we are going in the right direction. I think it’s a lot about awareness and communication and making things easily understandable for people. Giving people “aha” moments, when they learn something new and see how they fit into the bigger picture. That gives me hope that people will think more consciously about the way they live as a part of nature and the whole globe.