Modeling river basins is so fashionable it seems that that everyone wants in.

But the result has been a proliferation of models, some of which give conflicting results.

The aim is commendable though: to show the state of water resources in a given river. This ought to help decision makers develop the right policies to tackle poverty, for example; or where basins cross international boundaries, help them reduce the potential for conflict over water resources. They’re also useful in developing responses to challenges that will affect water availability and use, such as climate change.

But all of the models have their limitations, and it’s commonplace for multiple models to be developed for the same basin. So, when can we move away from modeling alone and focus on the increasingly importanttask of getting on with planning and management?

Robyn Johnston and Vladimir Smakhtin, scientists from the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), explore this in the paper, Hydrological modeling of large river basins: How much is enough? It has just been published in the Water Resources Management journal and is open access.

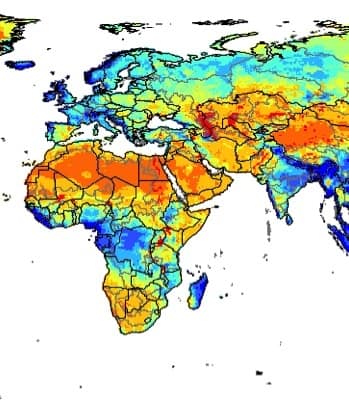

The authors draw attention to efforts made to model four major river basins, one of which is the Nile.

Biblical in proportion and notoriety, the Nile River Basin covers an area of over 3,000,000 km2 in no fewer than 11 countries, and is home to around 238 million people. Each country has valid reasons for laying claim to some of the water in the Nile, for developing irrigation systems or hydropower projects. That’s a cause of frequent flash points. For example, Egypt relies on the Nile River for 95% of its freshwater, while the vast majority of the water flowing in the River comes from Ethiopia, which needs water for agriculture and electricity generation. If there was ever a need to accurately model a river basin to assess the impact of particular policies on water users, it’s in the Nile.

And indeed, the Nile has been modeled several times over four decades, and to the tune of over USD 20 million. Thirteen separate models have emerged since 2000 alone, and new ones are still being developed. Some focus on the basin as a whole, others on sub-basins and more still on a purely national level. Some models work better than others, but a lack of data sharing and accuracy means there is frequent duplication of both effort and error. This means headaches for policymakers or, worse still, the wrong decisions being made.

The Nile is not alone. Similar issues affect attempts to accurately model the other major river basins in the study: the Mekong, Ganges and Indus. To improve the efficacy of river basin modeling and reduce duplication of effort, the authors make a call for more joined-up thinking in four main areas:

- Model inputs, data and results should be openly shared to allow more coordinated approaches and to capitalize on past efforts.

- Uncertainty in the models should be reported, so that the degree of confidence in the results can be taken into account in developing policies for river basin management.

- Data quality and quantity need to be improved for model inputs, calibration and validation.

- Within each major river basin, an appropriate agency should be identified and resourced to take responsibility for data sharing and coordination.

As the authors note, “Our aim… is to challenge researchers and funding agencies to give more consideration to the purpose of model applications; to their fitness for purpose in terms of temporal and spatial scale, and complexity; and to what extent they could build from existing work, rather than starting from scratch.”

It’s a call that requires modelers to take a step back from their screens and think about the bigger picture.

Johnston, R.; Smakhtin, V. 2014. Hydrological modeling of large river basins: How much is enough? Water Resources Management. DOI: 10.1007/s11269-014-0637-8

Robyn Johnston is Acting Theme Leader – Sustainable Agricultural Water Management at the headquarters of IWMI in Colombo, Sri Lanka

Vladimir Smakhtin is Theme Leader – Water Availability, Risk and Resilience at the headquarters of IWMI in Colombo, Sri Lanka