By Madhubanti Talukdar, Shibaji Bose & Deepa Joshi

This photo essay documents the lived experiences of local communities in the Indian Sundarbans, the magnitude of loss and damage, outcomes for lives and livelihoods, and the meanings and value attached especially to hard-to-quantify non-economic loss and damage.

The exacerbating climate crisis — marked by rising sea levels, erratic rainfall, recurrent and more intense cyclones and floods, and the repeated loss of land and homes to coastal erosion and salinization — threatens the lives and livelihoods of the millions of people who inhabit the Indian Sundarbans. For the already-displaced, the loss of identity and traditional ways of life has been particularly difficult to grapple with.

Gauhar Jan Bibi, 72, is an inhabitant of Lohachora, an erstwhile island in the Hooghly River within the Sundarbans Delta that used to be permanently flooded due to rising sea levels. She arrived at the Maheshtala resettlement colony in Sagar Island in 1984. She remembers when she went from being the daughter-in-law of a respectable, landowning family to a nameless, faceless refugee whose presence evoked only fear and mistrust, almost overnight.

“When we first came here, there was nothing — not a blade of grass in sight. We did not even have clean water to drink. When we requested villagers nearby to allow us to use their ponds, they mostly refused. They could not trust us, you see. They thought of us as thieves and dacoits [an armed robber].”

People living in the Sundarbans are often faced with the difficult choice of remaining trapped in a vicious cycle of poverty or leaving their homes for distant lands in search of work. The villagers of the once-prosperous Khashimara village on Ghoramara Island struggle against the increasing ferocity of cyclones and floods and with saltwater ingress which destroys standing crops and renders lands uncultivable for at least 2–3 years. Compensation is unequal and meagre, if even available. Losing one’s land has profound implications in rural India, where being bhumiheen (landless) does not merely signify landlessness but also the loss of pride and dignity.

For villagers like Purnendu Singh, migration is the only way to ensure that he and his family are able to sustain themselves and have access to basic needs, including healthcare. “We lost our betel leaf bareja (structures made of bamboo, straw, grass, and jute) to [Cyclone] Yaas in 2021, the year of the great flood. All our savings, amounting to approximately INR 1.5 lakh (USD 1,785) had gone into building the bareja. We had taken a huge loan that had to be paid off. The only way to cope with this loss was to leave home. My wife and daughter-in-law live in the village with my mother. My son lives with me in Kerala. Of course, I feel bad that we cannot be together but there is nothing that we can do about it. We have to survive!” says Purnendu, who, along with his son, was home for a short visit.

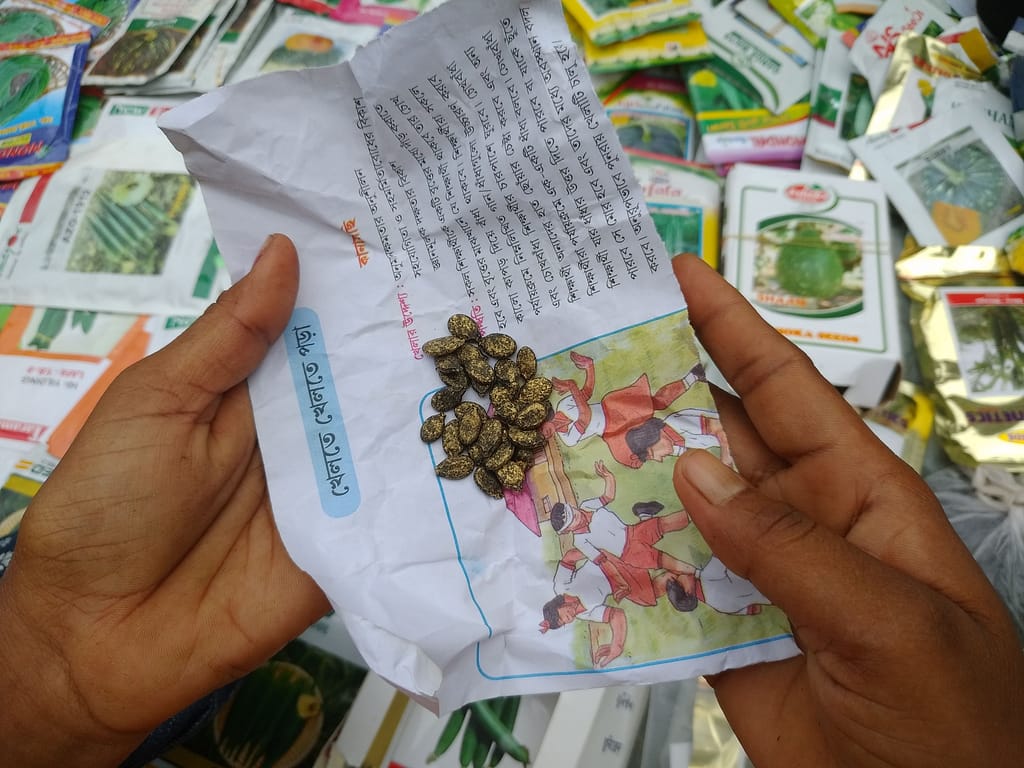

Villagers also speak of breakdowns in local, indigenous food systems. With the cultivation of traditional varieties of vegetables and foodgrains becoming unsustainable, there is an increasing tendency to cultivate only high-yielding varieties of crops (HYVs). These seeds require a heavy supply of fertilizers and pesticides, and impact soil productivity and water quality over time. The excessive dependence on HYV seeds, fertilizers and pesticides leads to an increasing reliance on the market for the farmer, raising input costs significantly.

With the disappearance of traditional varieties of food crops, familiar tastes, memories of food, and shared rituals around cooking and eating passed down through generations are slowly being erased, a form of loss and damage that cannot be quantified or compensated for.

Economic loss and damage in the Sundarbans is not limited to agriculture alone. An increasingly hostile environment means that other traditional occupations, like deep-sea fishing or venturing into the forest to collect firewood, honey, and crabs, become highly risk prone. Interacting with deep-sea fishers in Mayagowalini Ghat on Sagar Island as they stand mending a fishing net, we come to know how erratic rainfall, reduced fish yields, and changing river currents have pushed many into penury.

The constant uncertainty regarding one’s life and means forces the people of the Sundarbans to exist in a perpetual state of temporariness. The repeated loss of homes and property inhibits the building of anything permanent. As is seen in the above picture, a make-do Durga temple on Ghoramara Island, with paper pictures of the deity, replaced idols that were washed away during Cyclone Aila in 2009. These are the small and large changes that result in states of vulnerability and inability to feel settled that affect people’s mental health and wellbeing and disrupt their ability to make long-term plans and decisions regarding their lives.

The complex reality of people’s lives in the Sundarbans tells us that there is no easy way to assess or measure loss and damage. It manifests differently for different sections of the population, transforming significantly with time and social context. It is only by studying the phenomenon from the ‘bottom up,’ where the perceptions and voices of climate-affected communities take center stage, can one hope to address loss and damage with an underlying emphasis on climate justice.

This photo story is part of a study on climate change loss and damage in the Sundarbans commissioned by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and funded by the CGIAR Initiative on Securing Food Systems of the Asian Mega Deltas for Climate and Livelihoods Resilience.

* Names and locations have been changed to protect privacy.

Madhubanti Talukdar is an independent consultant and Shibaji Bose an independent research consultant, both based in Kolkata.

Ankana Das (IIT) and Tanmoy Bhaduri (IWMI) also contributed to this photostory.