International Women’s Day 2021

International Women’s Day 2021

Women in leadership: Achieving an equal future in a COVID-19 world

Every year men, women and girls push hard to achieve gender equality. The pay gap between men and women is over 30 percent, and the pandemic could set women’s careers back by as much as ten years as they returned to the home to become primary caregivers for their children. This year’s theme set by UN Women is: Women in leadership: Achieving an equal future in a COVID-19 world.

Across IWMI we’re celebrating the women who are leaders both in their families and their communities; we’re asking colleagues what they’ve achieved over the past 12 months, despite it being a tough year. Above all, we’ve shown the personal reserves of resilience and strength that women and men around the world have called on, and will continue to call on, to fight for equality, and to face an equal future together.

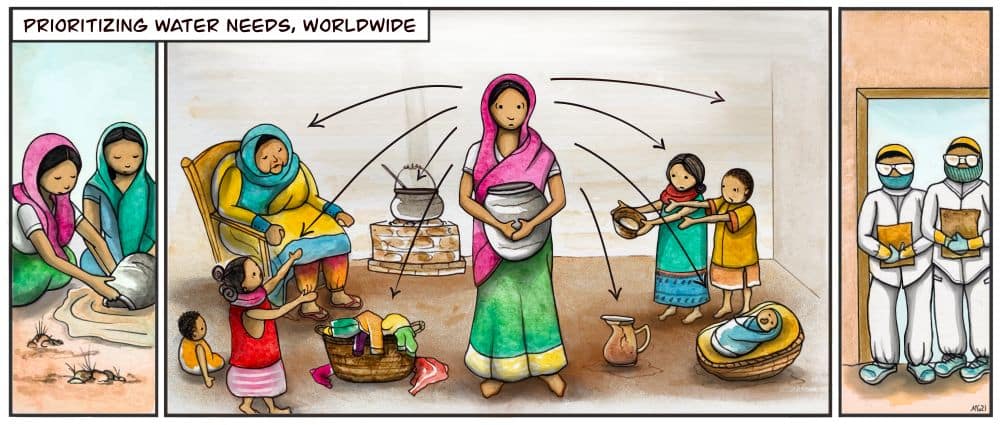

Women and water around the world

Worldwide, three billion people have no handwashing facilities at home, and two billion people use sources of drinking water contaminated by faecal matter. During the global pandemic, families must balance drinking and food preparation with sanitation and hygiene. Learn more about how IWMI’s work relates to Covid-19.

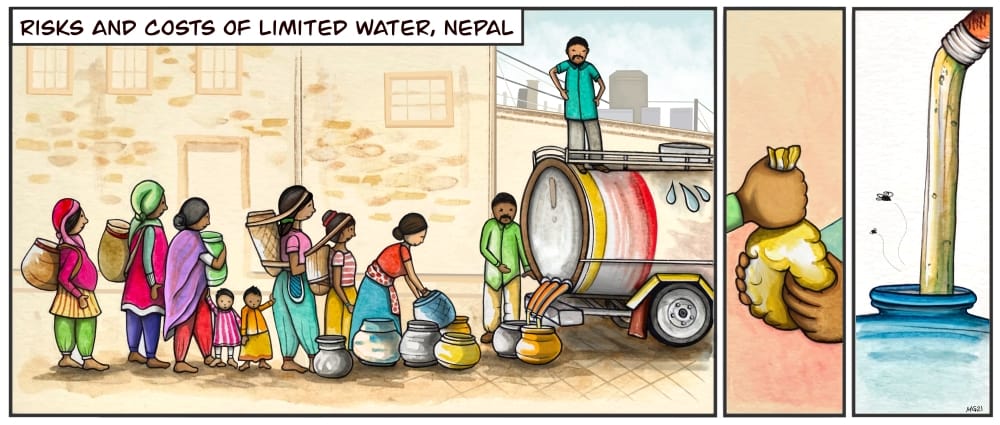

In Kathmandu, Nepal, water shortages are acute, and most households only get access to around an hour’s water supply per week from official or public sources. The alternative is a lifeline provided by vendors selling water from tankers which might be overpriced and is often polluted. It is common for families to spend around twenty percent of their earnings on water. Learn more about IWMI’s work on better WASH planning and financing, as well as how women are shaping water policy in Nepal.

International Women's Day 2021 Quiz

New landscapes of water equality and inclusion