By Gerald Atampugre, Olufunke Cofie and Seifu Tilahun

Feeding the world is no small task, especially with an ever-growing population in and around cities. Imagine a picture-perfect Ghanaian countryside filled with thriving farms, wetlands, and towns. Now, imagine these spots fading, threatened by overuse, climate change, and other challenges. That’s the current scenario in Ghana’s forest transition belt, a region vital for the country’s food and environmental health.

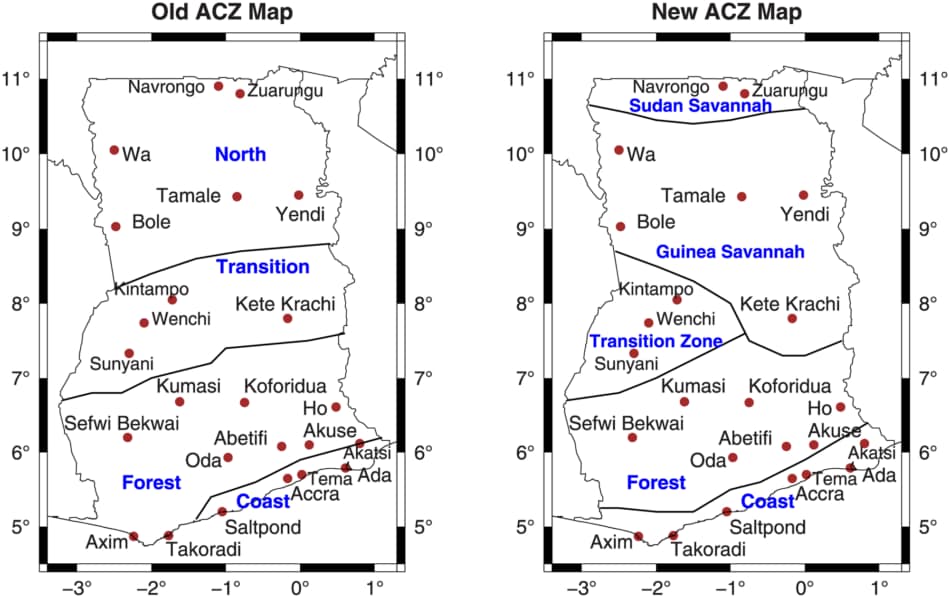

To give you a clearer picture, take a look at Map 1 showing the changing forest transition belt where the CGIAR Initiative on West and Central African Food Systems Transformation (TAFS-WCA) is working. It is obvious the old North Agro-Climatic Zone (ACZ) has split into Sudan and Guinea Savannah, with the latter expanding to cover more than half of the forest transition belt (in the new ACZ). These alterations are due to changing environmental and climatic conditions.

In simple terms, the critical landscapes—known as social-ecological production landscapes (SEPLs)—are facing a tough time. They include a mix of farmlands, ponds, wetlands, grasslands, and towns, all carefully balanced for the benefit of people and nature. Yet, over the years, factors like increased farming, logging, mining, and population pressures are making things hard for SEPLs.

Curious about how these landscapes have changed over time? Here is a visual representation, tracking the alterations from 2008 to 2021 (Map 2). Natural vegetation (both dense and sparse) lost the most to other land use/cover types within the period of study, with an alarming 13% rate of decrease per year.

![Source Map 2: Land use land cover change maps of the Mankran watershed in the Ahafo Ano South West District of Ghana (2008, 2015, 2018, and 2022]](https://mlpyskbirng6.i.optimole.com/cb:utH_.de5b/w:950/h:464/q:mauto/f:best/https://www.iwmi.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Picture1-e1701318104545.png)

If this continues, we risk not only the health of the environment but also the quality and availability of our food. But there’s hope on the horizon. Organizations such as the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) under the TAFS-WCA initiative are stepping in.

To understand the shared landscape vision guiding the activities of the TAFS-WCA initiative in the forest transition belt of Ghana, let’s zoom into the Ahafo Ano South West District in our next map.

TAFS-WCA, in partnership with the Ahafo Ano South West District Assembly, provided communities the platform to voice their perspectives and to co-design their own sustainable future. A series of workshop facilitated engagements with the communities to co-develop an Inclusive Landscape Management Plan (ILMP), as visualized in Map 3 above. It is all about listening, collaborating, and ensuring that the communities have full ownership and that their voices guide the strategies for a sustainable vision for their productive landscapes.

As part of the ILMP, the initiative is promoting smart, eco-friendly farming techniques and sustainable landscape management. For instance, in Ahafo Ano South West, a district within Ghana’s forest transition belt, innovations like the Black Soldier Fly larvae technology, integrated crop-fish systems and solar irrigation for cocoa are being tested and rolled out.

These innovations are all aimed at making the landscapes resilient to challenges including erratic weather and growing populations. And what is exciting is that they are not just top-down initiatives. These plans and innovations are being co-created with local communities, ensuring that everyone’s voice is heard and that the solutions are tailored to the unique challenges of each region.

So, what does the future hold? We need more such solutions—innovations that arise from a blend of science, local wisdom, and collaborative action. By adopting an integrated approach, we’re not just aiming for a sustainable future—we’re actively creating it.