Understanding Ethiopia’s past experience to guide future investments

Initiatives to restore degraded land on a large scale have gained huge momentum during recent years. The country-led African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR100), for example, seeks to reverse land degradation on 100 million hectares across the continent by 2030. This regional effort usefully complements the Bonn Challenge, which is working to restore 350 million hectares worldwide, also by 2030. Such initiatives foster hope that land restoration can not only help mitigate climate change through carbon sequestration but also improve rural livelihoods and spur growth by renewing the land’s productive capacity. At the same time, though, these efforts raise concerns about how best to restore degraded land and ensure equitable sharing of the benefits.

Learning from a leader

To better understand both the hopes and concerns, participants in land restoration initiatives would do well to examine closely the experience of Ethiopia. Its commitment to this task under AFR100 is the single largest, at 15 million hectares. The country has already invested heavily in programs to conserve soil and water, starting during the mid-1970s in response to severe drought and intensifying its efforts throughout the 1980s and 1990s, with substantial support from international donors.

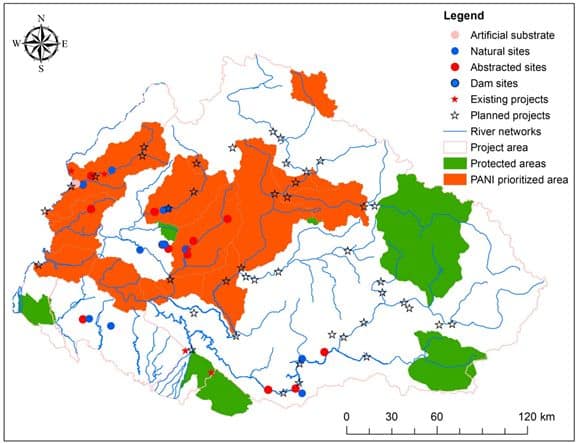

A new study carried out by IWMI researcher Zenebe Adimassu with two colleagues from European organizations should prove helpful to anyone desiring to know more about Ethiopia’s achievements. Titled Highlights of Soil and Water Conservation Investments in Four Regions of Ethiopia (Working Paper 182), the study offers an overview of this work for the period 1995-2014. It describes the various soil and water conservation measures used, and details the scale of investment in key agricultural regions, which account for a large proportion of the country’s land area and smallholder farmers. The study was conducted as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE), with support from CGIAR Fund donors.

It is not hard to see why Ethiopia has been compelled to lead the way in soil and water conservation. Throughout the country, exposed rocks and deep gullies offer proof of widespread topsoil loss, which accounts for the dun color of the nation’s major rivers during the rainy season. Researchers estimate that more than 300 million tons of soil are lost each year from the Nile River Basin in Ethiopia, of which about 45% winds up in the river system. The productivity losses caused by erosion cost the nation’s farmers an estimated USD 4.3 billion annually.

Getting a clear picture

Because of shifting approaches, differing units of measurement and inadequate documentation, it is hard to assess conservation efforts consistently and comprehensively across the whole country. Nonetheless, by studying cases in four key regions and by standardizing the data on the basis of person-days invested in conservation measures, researchers were able to form a clear picture of the scope and evolution of this work. They documented the use of numerous measures, consisting to a great extent of physical structures – such as bunds, terraces, ditches and waterways – aimed at enhancing farm and hillside management, and stabilizing gullies. The research also identified extensive tree planting and use of “exclosures,” which are plots of land that communities close off to grazing and other uses for land restoration.

Just in the last 3 years of the study period, farm and hillside terraces alone covered a conservatively estimated total of 6.4 million hectares across the four regions, or about 20% of Ethiopia’s agricultural land area. The average investment in such practices was highest in the Amhara Region and lowest in the Tigray Region, bordering Eritrea. Together, the four regions made an estimated investment of more than USD 1.2 billion per year over the last decade, obviously far below the annual cost of erosion to farmers.

What next?

Knowing how much has already been invested where, when and how is useful for deciding what must come next. But it is also important to know what impacts conservation practices have had on crop yields, soil conservation, water provision and other ecosystem services as well as the benefits that have accrued to the rural people depending on these natural resources.

Such information is unfortunately scant. So, a key recommendation of the study is to assign far higher priority to impact assessment. This measure should go hand in hand with the establishment of a formal nationwide system to monitor and document conservation efforts. The researchers further recommend greater efforts to complement the investment in physical structures with agronomic or biological measures, such as planting trees and grass strips to stabilize soil.

Prompt action along these lines will give Ethiopia a solid basis on which to identify successes and failures in soil and water conservation, offering valuable guidance for its own future investments and perhaps those of its neighbors.

Download the report

Adimassu, Z.; Langan, S.; Barron, J. 2018. Highlights of soil and water conservation investments in four regions of Ethiopia. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute (IWMI). 35p. (IWMI Working Paper 182). [doi: 10.5337/2018.214]