Groundwater research and practice

Soumya Balasubramanya and David Stifel

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects approximately 10% of the global population, and leads to 5-10 million deaths annually. Growing in importance is a distinctive form with unknown/uncertain etiology (CKDu), the cause of which remains unknown and is not linked to factors normally associated with CKD. Symptoms of CKDu manifest late, and are similar to late-stage CKD, complicating differential and early diagnosis and treatment. CKDu is prevalent in Nicaragua, El Salvador, India, Egypt, Sri Lanka and in several Balkan countries, with reported cases recently emerging in other countries in Asia and Africa.

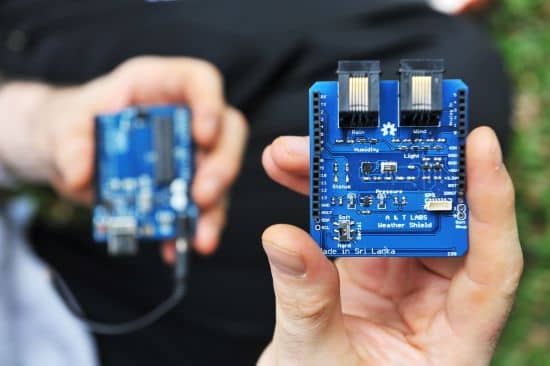

In Sri Lanka alone, around 150,000 people have been affected by CKD/CKDu, with CKDu primarily in rural communities that have historically used groundwater as their predominant drinking water source. A recent IWMI study finds that women may be more at risk of contracting the disease. These developments have required a public response in Sri Lanka, despite uncertainties regarding the causes of CKDu.

In line with the precautionary principle, the largest policy response in Sri Lanka has been to provide alternatives to untreated groundwater. The government has deployed several hundred public reverse osmosis (RO) units in affected areas, including at schools and religious institutions. In addition, rainwater harvesting units, and tanker services that convey drinking water to the storage tanks of households have also been financed. IWMI’s research shows that there has been a significant rise in the uptake of RO water as a primary drinking water source, from 1% of household in 2013 to over 50% by 2018.

Improving equity in relation to sustained provision of RO water is critical for policy. While some households are provided RO water free of charge, others have to pay for it (~LKR 1-4/liter, which is 8-10 times higher than what urban households pay). As piped water schemes are deployed in the future, interim measures such as ensuring repair and maintenance of existing RO systems and regulating quality of treated RO water will be important for public health outcomes. Finally, examining the health and non-health impacts of these RO systems will be important for informed decision-making.

Understanding the risk factors associated with the disease is also important for guiding public resources. IWMI recently studied the historical behaviors pertaining to drinking water sources, water treatment practices, and agrochemical use of groundwater-dependent households in CKDu-affected districts of Sri Lanka; and also undertook a basic program of water-testing. There were no discernible systemic differences in the patterns of drinking water choices and behaviors of affected and unaffected households over the 18-year period from 2000 to 2017. There were indications, however, that CKD-affected household were more likely to have practiced agriculture and were poorer. The results suggest that groundwater sources and treatment practices may not be the sole risk factors, and further research is needed to better understand how water quality, including organic and inorganic contaminants, may relate to CKDu.

Governments in CKDu-affected countries are not in a position to sit idle while the jury remains out. Targeted research for policy can help with decision-making even under uncertainty.

Soumya Balasubramanya is Research Group Leader in Economics at the International Water Management Institute—CGIAR. David Stifel is Professor of Economics at Lafayette College, and currently a Sabbatical Research Fellow at the International Water Management Institute—CGIAR.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the International Water Management Institute.